Secondary menu

“2030 is our last chance”: The Right to housing to ensure no one is left behind

Lauren Pinder (3L)

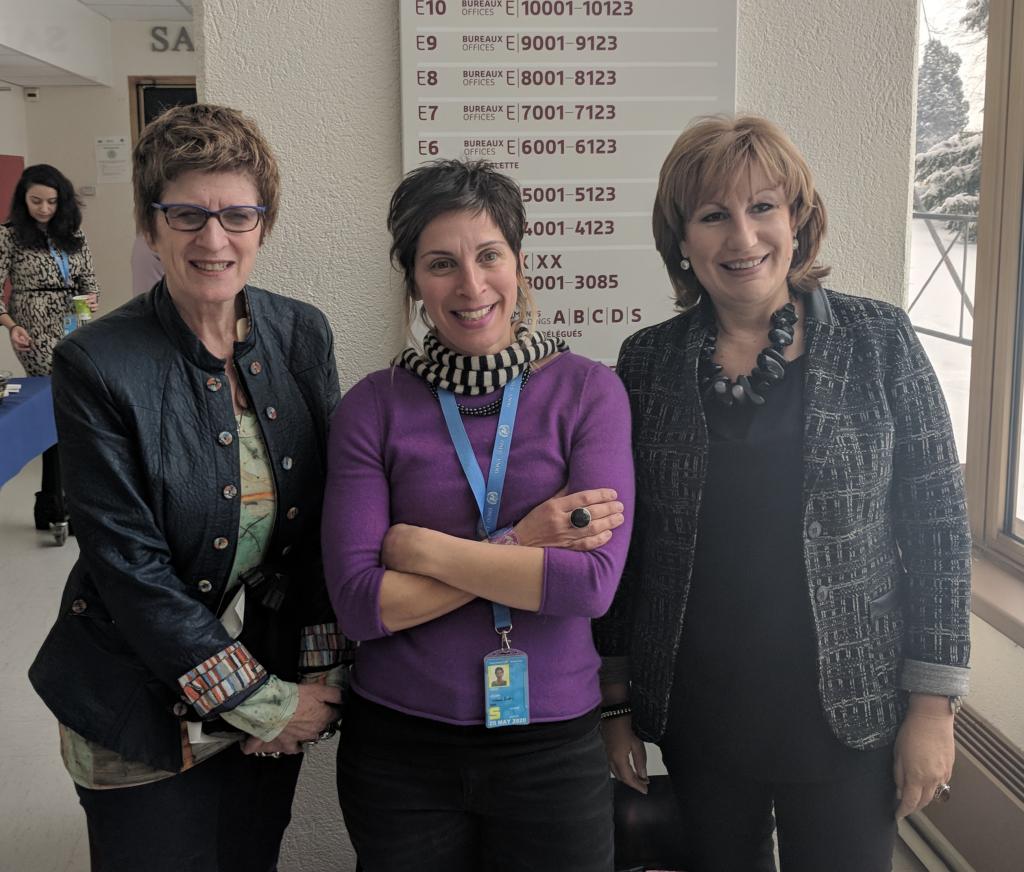

Dumbstruck with excitement, and a bit jet lagged. That’s how I would describe the feeling I had as I hustled into a side meeting at the 37th Session of the UN Human Rights Council in Geneva. Around the table sat Leilani Farha, the UN Special Rapporteur on the right to housing, Kate Gilmore, the Deputy High Commissioner for Human Rights, and Emilia Saiz, the Secretary General of United Cities and Local Governments (UCLG). These three women represent the founding partners of The Shift - the movement to reclaim and realize the right to housing. On that afternoon, in that room, they met to discuss last minute preparations for their panel on how to #MakeTheShift.

What brought these three committed advocates together on a snowy day in Geneva was the same thing that brought states together in 2015 to commit to the Sustainable Development Goals: the path that the world is moving down is untenable. As the population increases at an unprecedented rate, so too does global inequality, with recent estimates stating that the 42 richest people in the world hold as much wealth as the 3.7 billion poorest. Climate change, natural disasters, pollution, and failing infrastructure have a disparate impact on the world’s poor and marginalized, as their access to universal human rights is in many ways non-existent.

In response to these nightmarish realities, governments and civil society created Agenda 2030. Agenda 2030 includes a list of commitments that states must achieve to end poverty and save the planet, with the pledge that “no one be left behind”. It has been three years since the world embraced these ambitious and necessary commitments. There are now only 12 years until the deadline. Cognisant of this fact, I can’t shake something I had overheard a national human rights commissioner say that week: “2030 is our last chance.”

So, what does this have to do with the right to housing? Simply put, housing as a human right is the vehicle for ensuring equality, and equality is necessary to ensure no one is left behind. Adequate housing is integral to ensuring health, life, community, sustainability, and ultimately, to protecting human dignity.

But when treated as commodity, housing embeds and exacerbates the very inequality Agenda 2030 seeks to address. Financialization of housing equates homes to safety deposit boxes for corporations and the rich, while low and middle-income families are priced out of their homes, out of communities, and out of cities. The result? More and more people finding themselves turning to sidewalks, parks, overcrowded apartments, unsafe houses, and informal settlements to rest their heads.

Enter The Shift.

In response to the financialization of housing and the coinciding housing crisis, Ms. Farha, the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, and UCLG founded The Shift. The Shift brings together actors from around the world and from various sectors including national and local governments, architecture, urban planning, and finance – all united in the rejection of housing as a commodity and all committed to meeting Agenda 2030 and SDG 11.1 – adequate housing for all. But making global change requires allies from around the globe; Shifters, if you will.

At the #MaketheShift panel during 37th Session of the Human Rights Council, the South African Human Rights Commissioner, Mohamed Ameermia joined panelists to speak to state officials and civil society representatives about the role that they all must play in realizing the right to housing for all. At the panel, 12 states were represented (including Germany, Namibia, and Finland, each of whom supported the event), alongside various civil society representatives.

Right to Housing Mandate Team on the way to the Panel

Deputy Commissioner Gilmore opened the panel, inviting the room to “understand the home as a rights-based place” and calling on everyone to “prevent urban spaces from becoming prisons of poverty and entrenching inequality.” Secretary General Saiz reminded the audience that “[i]t’s not a global north problem. It’s not a global south problem. It is a universal problem.” Homelessness exists in every country. Some of the richest countries in the world are home to sprawling informal settlements. States in the global north, despite their wealth and resources, have shirked their right to housing obligations, actively supporting the profit-making of corporations and financial institutions instead of promoting inclusive housing systems.

The panel as Deputy Commissioner Kate Gilmore delivers her opening comments

This is not surprising to those of us living in Toronto, where walking past homeless people and hearing about the unaffordability of rent is normalized. But when people around the world hear of individuals sleeping outside when it’s -10 or -20 in a country as wealthy as Canada, they are shocked. And they are right to be. The cruelty of the deepening issue must be understood as a clear violation of human rights.

A core component of the panel discussion was the necessary and collaborative roles that all actors must play to address this human rights crisis. This is different from the standard discussion at the UN that almost exclusively focuses on national governments. The Shift recognizes collaboration between all sectors and actors as the strongest asset, and necessary to realizing the right to housing universally.

Commissioner Ameermia, speaking from his position within the human rights system, stated that “national human rights institutions must play a key role in reclaiming the right to live in dignity and comfort and in meeting SDG commitment to adequate housing by 2030.”

The crucial role of local governments, over 200,000 of which are represented by UCLG, was emphasized by the panel. Local governments are often responsible for housing, as well as zoning, transportation, services, and local infrastructure. These are all necessary elements to fulfilling the right to housing. And of course, a discussion on reorienting housing systems would be utterly incomplete if it did not address the role of private actors.

At the general Human Rights Council session the previous day, multiple state delegates stood up and outlined that they would be relying on private actors to fulfill their right to housing obligations, to address housing shortages, and to provide affordable housing. Financial institutions, developers, and investors occupy a dominant space in housing. Some, such as the private equity firm Blackrock Inc., have taken the position that they have a social responsibility in their operations. But overwhelmingly these actors are responsive only to the profit they stand to make. And in housing, they stand to make a lot. The Shift invites all actors to recognize how they engage with the right to housing, and to adjust practices accordingly.

While corporations’ narrow focus on profit may not change, Ms. Farha emphasized that states have the duty under international human rights law to ensure that the actions of the private sector are oriented toward the right to housing. Where they are relying on corporations to finance, build, and manage housing, states remain accountable to human rights law and must regulate accordingly. As Ms. Farha put it: “States cannot contract out of human rights.”

As the panel closed, stakeholders in the room appeared motivated to work toward the realization of the right to housing and making housing systems work for everyone. This echoed my experience in the earlier meetings and events that week. If 2030 is our last chance at ensuring no one is left behind, I find comfort in knowing that these individuals are leading the global efforts to Make the Shift. Here in Toronto, we can be Shifters by participating in the current consultation on National Housing Strategy - telling the federal government that though laudable, it is not sufficient to say it is a rights-based strategy. It needs to recognize the right to housing as a claimable and legally protected right; and ensure that the no one is left behind by ending homelessness and its structural causes by 2030.

Representatives of the three founding partners of The Shift