Secondary menu

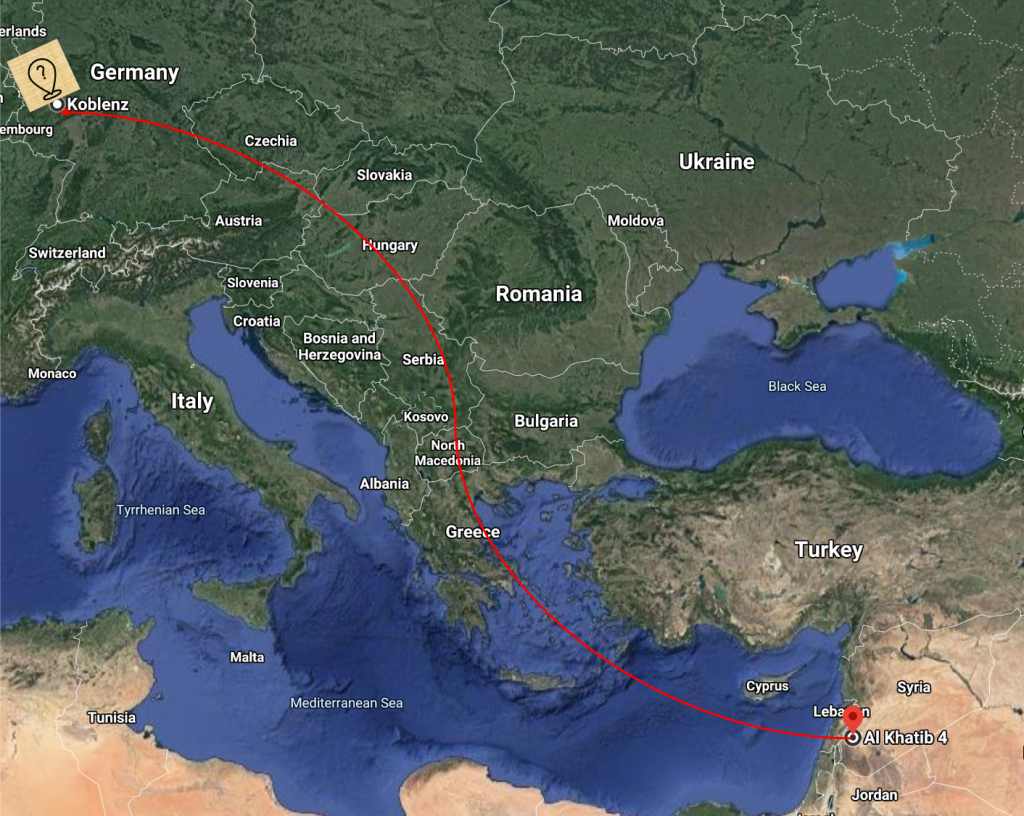

From Al-Khatib to Koblenz

Photo credit: Taskeen Ather Nawab and Google Maps

In Damascus,where Baghdad Road purportedly meets Al-Khatib Street and where the red Crescent Hospital sits, lies Branch 251 of Syria’s General Intelligence Directorate — or “al-Khatib” — a state security interrogation centre known to its survivors asHell on Earth.

Last month, in a court about 4000 km away in Koblenz, Germany, following 11 months of proceedings, a convictionhailed as a landmark in the pursuit of justice for violations committed in the Syrian civil war was brought against former Syrian intelligence officer Eyad al-Gharib. In autumn of 2011, the relatively lower level employee of the branch subdivision was found searching the streets with colleagues for anti-government demonstrators, with knowledge of what happened within the centre. At least 30 of whom he captured and busted to al-Khatib. On February 24 2021, al-Gharib was sentenced to four and half years in prison for aiding and abetting crimes against humanity, including torture and deprivation of liberty.

al-Gharib was one of two defendants in this case — the other being Anwar Raslan, whose trial is still on-going. Raslan, allegedly the man “with an office on the first floor, who ran the place and directed the torture” is directly charged with crimes against humanity, particularly the oversight of 4000 counts of torture and 58 counts of murder, amidst charges of rape and sexual assault. Survivors document beatings en route to the centre, a “welcoming party” of the same on arrival, electrocutions, falling asleep with backs and hands bound by cables, and waking up to sounds of screams.

Background

Reports of a network of underground prisons corroborate these narratives. Accounts includethose of Syrian human rights lawyer Anwar al-Bunni, who was especially instrumental in rounding up witnesses for the trial and had been detained at al-Khatib for five years and eight days before fleeing Syria for Germany. Evidence laid out at trial included a grave digger’s testimony of the mass graves atal-Qutayfah and Najha, documenting the arrival of an average of 700 bodies per truck four times a week from various state security facilities. In total, over a million dead bodies were counted with physical signs of lacerations and removed nails.

With horror of this scope underpinning the overall conflict, how does the conviction of al-Gharib, an effective middle-man, signify a turn in the pursuit of justice for atrocities committed in Syria?

According to Patrick Kroker, senior legal advisor with the European Center for Constitutional and Human Rights, the case was the first to reveal in-depth information about the inner workings of the Syrian government’s detention centres. It was also the first instance of a former Syrian official [involved in the Syrian civil war] being held accountable.

The plethora of evidence from a government institution combined with the indictment of a government official appears to suggest to commentators a systematic attack orchestrated by the Assad regime, instead of the crimes before the court being independent instances of torture and murder. The Assad regime holds, however, that they do not have a torture policy and are holding terrorists to account, while claiming no ownership of the “torture archipelago.”

Decoding Universal Jurisdiction

These details give rise to the question of Germany’s assertion of authority over the case. Given its pioneering character, why was the trial not conducted before the International Criminal Court (ICC), and instead held in the small town of Koblenz, and why does it matter?

As Syria is not a party to the Rome Statute, only a referral to the ICC by the UN Security Council can lend the court jurisdiction. However, when the draft resolution calling for an investigation into alleged war crimes on both sides was brought before the Security Council in 2014, China and Russia vetoed the resolution arguing that it communicated a one-sided account of the alleged atrocities.

It was not until 2019, when al-Bunni saw and recognised Raslan, who had ordered his arrest and detention at al-Khatib in 2006— first in the refugee centre in Berlin, and then again in a furniture shop — that the case was brought to life in the international arena.

The German court’s claim rests in the legal principle of “universal jurisdiction.” The Völkerstrafgesetzbuch, or the Code of Crimes against International Law, allows for cases to be prosecuted under international criminal law provisions even where the defendants and crime are foreign to the land — under the rationale that some crimes are hostis humani generis, i.e., an enemy to all people, and override most considerations of sovereignty.

Critically, the principle of universal jurisdiction predates the fully-fledged functioning of the ICC. Germany incorporated universal jurisdiction into its domestic law in 2002 in accordance with the Rome Statute of the ICC, covering the offences of genocide, crimes against humanity, and war crimes. Beyond this, Germany’s authority over al-Gharib and Raslan’s case is bolstered by the fact that the heim (“hearth” in German) welcomes many Syrian refugees, and that these asylum-seekers require some form of access to justice.

However, the national court’s authority over any foreign case appears suspect when viewed through the selective manner in which it has historically been exercised. While several nations have adopted the principle, Germany demonstrates an example of its selective application. The German Federal Prosecutor’s 2005 and 2006 decision not to open investigations into senior US officials for alleged abuses of detainees at Guantanamo Bay in Cuba, and Abu Ghraib in Iraq, reflect the influence of political considerations on prosecutorial discretion under universal jurisdiction. Where diplomatic relations are fractured, as has been the case with Germany and Syria since 2012, prosecution becomes easier.

Counterintuitively, the ICC’s statute situates it with a supplementary role to that of nations— driving nations to prosecute criminals where the crimes were committed. The historical roots of universal jurisdiction in piracy law further detract from its justification through the singular lens of the enormity of the crime committed. Commentators have drawn attention to the dual character of piracy, highlighting thelocus delicti of the offence — i.e., its transnational nature — a procedural justification for universal jurisdiction rather than the substantive justification of hostis humani generis. Would Raslan and al-Gharib’s alleged crimes, all of which were committed on Syrian soil, qualify under that procedural justification?

Another consideration that necessarily calls universal jurisdiction outside the ICC into question is the application of different criminal codes to the trial, depending on which nation prosecutes the crimes. The evidence levelled against al-Gharib in court was largelydrawn from his own admissions when he defected from the regime and entered Germany, and was essential for his convictionunder the principle of immediacy in German law. What would the evidentiary standard have been before a different national court that had adopted universal jurisdiction? If a nation other than Germany successfully revived the charges against US officials being held to account for Guantanamo Bay and Abu Ghraib, would they be subject to the same standards under a different law? Does that differential application of justice meet the borderless outrage understood to be produced by the enormity of such crimes?

The same critique of selective application of justice for egregious crimes can be brought against the ICC and the UN at large. However, China and Russia’s veto of the 2014 resolution demonstrates an infinitesimally higher capacity in such spheres to carry out a more balanced fight against impunity relative to national courts.

On February 25, with respect to al-Gharib’s conviction, the UN Human Rights Commission tweeted that “with no international process under way, fair national courts can and should fill accountability gaps for such crimes, wherever committed.” It has been heartening for the survivors of Branch 251 to see the beginnings of justice underway, however symbolic. In this instance, as in previous instances of the application of universal jurisdiction in Germany and elsewhere, it is an avenue for those who have no other recourse to justice.

It is perhaps a reach, however, to suggest that accountability gaps ought to be filled by national courts in a conflict of this scope and complexity. A proper extension of justice here would ideally leverage the intrinsically reduced bias of supranational courts to develop a prosecutorial capacity unmarred by differentiating diplomatic ties or criminal codes — and would certainly not hinge on a chance encounter between a defecting perpetrator and his ex-victim.