Secondary menu

Creative Dissent

Free expression rights, the Winter Olympics, and failures to protect the arts

Last month, George Washington University (GWU) became the latest arena for the censorship of the arts, drawing to the forefront once again the vulnerability of artists’ freedom of expression.

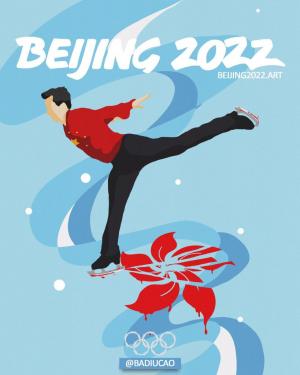

The controversy surrounded the display of Chinese artist Badiucao’s poster series commenting on the Beijing 2022 Winter Olympics. In a sequence of five works, the artist draws imagery from the biathlon, curling, hockey, snowboarding, and figure skating events. He then alters each image to visually critique the Chinese government’s persecution of Tibetans and Uyghurs, the dismantling of Hong Kong’s democracy, and the lack of transparency surrounding the pandemic. Badiucao later added to his core series with additional works, one of which places the famous 1989 image of “Tank Man” in front of a bobsledding team.

Since his release of the posters online in the fall of 2021, Badiucao has actively encouraged the public to download, print, and disseminate these images. The response has evolved into a global movement. This campaign ran parallel to states’ diplomatic boycotts of the Olympics led by the US, Canada, Australia, and the UK. Badiucao hoped to bridge the “gap between the general public’s understanding [of human rights violations committed by the Chinese government] and policymakers’ decisions” to boycott the event. His art quickly made its way from a first display at the October 2021 Oslo Freedom Forum conference in Miami to major cities across the world.

In early February, anonymous students pasted printed sheets of Badiucao’s artworks on bulletin boards and poles around the GWU campus. The posters were quickly met with complaints from other students, sent via email to University President Mark Wrighton. Wrighton replied that he too was “personally offended” by the posters and would work to have them removed “as soon as possible.” In a Twitter thread on February 4, Badiucao criticized Wrighton’s support for the removal of his posters and the University's decision to investigate those responsible for displaying his art. Badiucao’s work is not new to controversy – this incident comes on the heels of the Chinese Embassy in Rome’s attempts to shut down the artist’s first solo-exhibition in Brescia, Italy this past fall. Despite intimidation, Museo di Santa Giulia trail-blazed ahead.

Under Articles 19 and 27 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression, as well as the right to freely participate in the cultural life of the community and to enjoy the arts. Yet Wrighton’s knee-jerk reaction speaks to the unique vulnerability of artistic expression to censorship. Perhaps even more so than free speech controversies and the exchange of words, there are no bright-line rules in the arts. Visual communication cuts across language barriers while leaving ambiguities in interpretation. Wrighton’s response is in many ways analogous to that of the Customs officers in Little Sisters Book & Art Emporium v Canada, 2000 SCC 69, who testified that they made no attempt to “judge the political, artistic, or literary merit of a particular work” prior to seizure.

These default, knee-jerk reactions to the arts are widespread. Just a year ago, Nick Cave successfully defended his work, Truth Be Told, as art, not a sign, in front of the Kinderhook, New York zoning board and blocked attempts to remove the installation for violating building codes. One board member commented that Cave’s work reminded him of Picasso’s Guernica –“[it] made a powerful political statement, and it was art.” These cases and Wrighton’s inadvertent censoring highlight the level of discretion involved here: what qualifies as “artistic merit” to be protected? Groups from all ends of the political spectrum have latched onto the GWU incident. But at its core it seems clear that Wrighton curtailed the expression of both Badiucao and the students who displayed his posters in protest of the Winter Olympics.

The GWU incident is only the most recent flashpoint in the global targeting of artistic expression. Last summer, police raided a Hong Kong art gallery hosting an exhibition dedicated to the 2019 pro-democracy protests. Activist Elżbieta Podleśna recently marked the anniversary of her acquittal on charges of “desecration” and “offending religious sentiment” for depicting the Madonna and Child image with rainbow halos in support of LGBTQ+ rights in Poland. Hundreds of artists have been detained and censored in efforts to quash anti-government protests in Havana, Cuba. As the world turns its focus to Russia’s ongoing invasion of Ukraine, installation artist Luba Drozd reminds us of the critical role artists play in documenting conflict. On President Vladimir Putin’s aggression, she notes, “we [artists] have been screaming into the void for years.”

Wrighton ultimately backtracked from his initial position, acknowledging in a February 7th statement to the GWU community that his “hasty” reactions to the posters were mistakes: “creative art is a valued way to communicate on important societal issues.” In response to the incident, Badiucao offered to meet with students who found his work offensive and has remained willing to hold an open dialogue on his criticism of China’s policies. He also suggested the works be given a permanent display space on GWU’s campus.

The Winter Olympics are now long over, but the posters were never re-hung.