Secondary menu

Fear Above Science: Canada's Ebola Related Visa Restrictions

By Michelle Hayman, 2L

On October 31, 2014, Citizenship and Immigration Canada (CIC) announced new travel restrictions for individuals from countries facing outbreaks of the Ebola virus. CIC stopped processing both new and existing visitor visas, as well as permanent residence applications from individuals who had been in an Ebola-affected country within the previous three months. The policy contains an exception for Canadian health workers aiding in the efforts to stop the disease. Around thirty countries, including Australia, have introduced similar Ebola-related travel restrictions.

On October 31, 2014, Citizenship and Immigration Canada (CIC) announced new travel restrictions for individuals from countries facing outbreaks of the Ebola virus. CIC stopped processing both new and existing visitor visas, as well as permanent residence applications from individuals who had been in an Ebola-affected country within the previous three months. The policy contains an exception for Canadian health workers aiding in the efforts to stop the disease. Around thirty countries, including Australia, have introduced similar Ebola-related travel restrictions.

The World Health Organization (WHO) has criticized CIC’s decision and continues to recommend against travel and trade restrictions. However, Canada’s ban remains in place, raising a number of in- ternational law and public health concerns.

The International Health Regulations

Canada is one of 196 signatories to the International Health Regulations (IHRs). The IHRs foster global cooperation “to prevent, protect against, control and provide a public health response to the international spread of disease in ways [...] which avoid unnecessary interference with international traffic and trade.”

The IHRs require any restrictions on travel or trade related to disease outbreaks to be made based on scientific principles or a WHO recommendation. This evidence-based approach attempts to address the economic incentive some countries may have to initially hide disease outbreaks from the global community. In fact, Canada played a key role in updating the IHRs following the outbreak of SARS in 2003, when it suffered economic losses related to a WHO travel advisory against Toronto.

CIC has yet to publically provide a scientific basis for introducing the Ebola-related ban, contrary to the WHO recommendations. However, the Canadian government maintains that its measures do not violate the IHRs, as they do not prevent Canadian medical professionals from going to Ebola-affected regions.

Regardless of this exception, travel bans such as these will likely reduce future international trust in the relevance and power of the IHRs. Countries may once again have an economic incentive to withhold information about early disease outbreaks from the WHO in order to avoid travel and trade repercussions. As a recent article in the Canadian Medical Association Journal argues, these bans “unravel the global social contract” central to fighting infectious diseases.

Poor Public Health Evidence

Moreover, visa restrictions are unlikely to help contain disease out- breaks. WHO representative Dr. Isabelle Nuttall released a statement cautioning against these restrictions, as “it is impossible to stop the movement of people motivated to see loved ones or seek a better life for their children.” Visa restrictions simply force indi- viduals to find new ways of travelling and make tracking disease transmission more difficult.

A recent study published in the Lancet found that the majority of air travellers departing Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone (Ebola- affected countries) travel to other low-income and lower-middle-income countries, with very few travelling directly to Canada. The study urged wealthier nations to help finance exit screening at international airports in the Ebola-affected nations, rather than imposing travel bans.

While visa restrictions may provide a false sense of security for Canadians, they ignore the greater likelihood that Ebola will travel to countries with poorly resourced public health systems, possibly leading to further spread of the disease.

Studies have shown that similar bans are ineffective at preventing the transmission of other diseases. In the 1980s, governments around the world, including Canada, created immigration and travel restrictions against persons living with HIV. As early as 1987, WHO studies found that these restrictions were ineffective and potentially counter-productive in reducing the spread of the disease. A recent systematic review by the WHO found that travel restrictions were similarly ineffective at preventing the dissemination of influenza. Thus, in addition to the Ebola visa restrictions imposed by Canada and Australia having potentially serious negative economic effects on countries in Western Africa, studies such as the above indicate that they are also unlikely to play a positive role in combating the virus.

Even if travel restrictions were found to be effective, Canada’s policy goes far beyond the least restrictive means. For instance, it blocks applications from anyone who has been in an Ebola affected country within three months prior to the date the application is received by CIC, more than four times the length of the 21 day incubation period of the virus. By contrast, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention considers a national Ebola outbreak to be over when 42 days have passed since the last patient in isolation became Ebola Virus Disease negative.

Canada’s restrictions clearly contradict scientific evidence on disease containment. Moreover, the policy contributes to the weakening of one of the most important legal instruments supporting global cooperation in disease control, the IHRs. If the Canadian government truly wants to combat Ebola, it must overturn its damaging visa restriction policy, and instead promote the development of health infrastructure in the countries most affected by the disease.

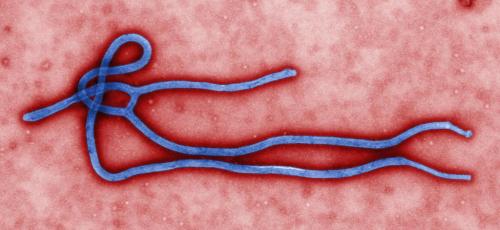

Photo: The Ebola virus (Credit: CDC Global, Wikimedia Commons)