Secondary menu

Justice, Reconciliation, and Everything in Between: The Issue of Japanese Military Sexual Slavery

Daniel Ki-Won Moon (2L)

Last June, I witnessed people young and old gather every Wednesday in front of the Japanese Embassy in Seoul, to demand a formal apology and reparations for the over 200,000 women who were coerced into military sexual slavery by Japan between 1932 and 1945. These victims were euphemistically called ‘comfort women’. From May to July 2018, I had the opportunity to research the issue in China, South Korea, and Japan with the generous funding of the International Human Rights Program and the support of ALPHA Education.

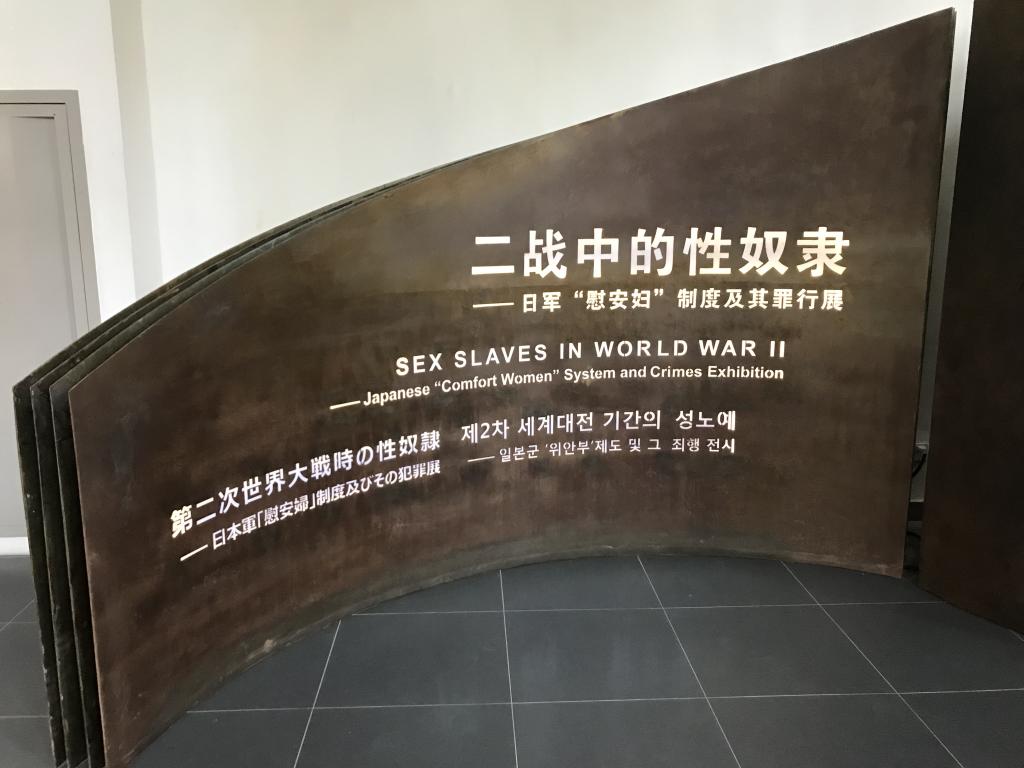

‘Comfort Women’ Museum in Nanjing, China. Credit: Daniel Ki-Won Moon.

‘Comfort Stations’ in Asia

When Nanking fell to Japan in 1937 during the Sino-Japanese War, an estimate of 200,000 to 300,000 people were indiscriminately massacred and thousands were raped by the Japanese Imperial Army. The news of these atrocities sparked outcry from the international community. In response, Japanese officials instigated a wide-scale expansion of ‘comfort stations’, which were military controlled facilities where victims of Japanese military sexual slavery were confined, tortured, and raped. Recruitment often involved abduction and deception. According to Carmen Argibay, “[by] confining rape and sexual abuse to military-controlled facilities, the Japanese government hoped to prevent atrocities like the Rape of Nanking or, if such atrocities did occur, to conceal them from the international press.”

While most of the victims came from Korea and China, many were also taken from the countries and territories occupied by the Japanese forces in Southeast Asia and the Pacific. By 1945, Japan had established ‘comfort stations’ throughout a vast part of Asia, including China, Singapore, Taiwan, the Philippines, British Malaya, New Guinea, and Truk Island.

Road to Justice: Legal History and Challenges

After Japan’s unconditional surrender, the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal was convened in 1946 to prosecute leaders of the Empire of Japan. At the tribunal, the crime of military sexual slavery was never addressed, and it was largely ignored by Japan and the international community until Kim Hak-Soon broke the silence in 1991 by going public with her testimony. Her bravery inspired a series of lawsuits against the Japanese Government and prompted other survivors to come forward. To this day, however, none of the ‘comfort women’ lawsuits brought before the Japanese judiciary have succeeded. While recognizing the veracity of the plaintiffs’ factual claims, Japanese courts dismissed the claims on procedural grounds, such as the waiver of claims under treaties.

Japan has signed a number of treaties that purport to provide redress for its wartime action, such as the 1951 San Francisco Peace Treaty, the 1965 Japan-Republic of Korea Agreement, and the 1972 Sino-Japanese Joint Communique. In the ‘comfort women’ lawsuits, the Supreme Court of Japan and lower courts held that the treaties extinguished the claimants’ right to bring substantive claims, while the Supreme Court of Korea ruled last October that the San Francisco Peace Treaty and the 1965 Agreement did not waive the right of plaintiffs in that case to sue a Japanese steel company responsible for their forced labour during WWII. In his concurring opinion, Justice Lee Kitaek opined that the treaties, at most, waived South Korea’s right to diplomatic protection— that is, the right of South Korea as a state to bring claims on behalf of its national citizens who were injured by Japan’s illegal acts— and not the claimants’ right to a civil action.

Recent Developments

In a 1996 report on the issue of Japanese military sexual slavery, the UN Special Rapporteur on violence against women, its causes and consequences, Radhika Coomaraswamy, urged Japan to (1) acknowledge its violations of international law and accept legal responsibilities; (2) pay compensation to the survivors; (3) make a full disclosure of documents and materials in its possession regarding ‘comfort stations’; (4) make a public apology in writing to individual victims; (5) raise awareness of the issue by amending educational curricula; and (6) as far as possible, identify and punish perpetrators.

In 2015, the now-impeached President Park Geun-Hye of South Korea and Prime Minister Shinzo Abe of Japan announced that they had come to an agreement whereby Japan would provide a one-time monetary contribution of approximately 12 million CAD to establish the “Reconciliation and Healing Foundation” for the survivors of Japanese military sexual slavery. The agreement was purely verbal and was to be a “final and irreversible resolution.” It was met with heavy criticism in South Korea for lacking crucial elements of the victims’ demands — a proper apology and reparations.

In January 2018, the newly elected South Korean government urged Japan to provide a fresh apology and announced in November that the “Reconciliation and Healing Foundation” would be dissolved. In essence, the government revoked the agreement previously made by former President Park and Prime Minister Abe. Around the same time, the UN Committee on Enforced Disappearances observed that the issue of Japanese military sexual slavery was not finally and irreversibly solved.Japan, nonetheless, maintains the position that the 2015 Agreement settled the issue.

Closing Remarks: The Road Ahead

Last May, I left for Asia with the aim of producing educational material for ALPHA Education discussing the legal issues at stake in the issue of Japanese military sexual slavery. Over 2.5 months, I travelled to China, South Korea, and Japan in order to engage more directly with the issue and to witness current developments in the three countries. I visited museums, met with surviving victims, interviewed professors, researchers, and activists, participated in the weekly protests, and interned at an advocacy NGO for the surviving victims.

In my conversation with attorney Kang Jian, who played an instrumental role in bringing Chinese ‘comfort women’ lawsuits against Japan, she suggested that legal avenues for redress were no longer available. Instead, she emphasized the importance of education. During my time in South Korea, I witnessed hundreds of elementary, high school, and college students come out to the Japanese Embassy every Wednesday to participate in the weekly protests. I believe that their active advocacy efforts demonstrate the power of education.

During the last days of my fellowship, I asked professor Kimura of Seinan Gakuin University in Japan about what motivated him to conduct research into victims of Japanese military sexual slavery in Indonesia. His answer was simple: it is a human rights issue. To that end, I believe that Canada’s moral and human rights obligations call us to direct our attention to the issue. Perhaps, it begins with education. The executive director of ALPHA Education, Flora Chong, has often said that the history of World War II in Asia is neglected in Western societies.

Last summer, there were 28 surviving victims in South Korea, five of whom I had the chance to meet. Today, there are 23. In what will likely be a long and arduous battle, it is incumbent on present and future generations to resolve the issue. It is my hope that through continued research and education, the global community can produce the impetus to deliver overdue justice.

ALPHA Education (Association for Learning and Preserving the History of World War II in Asia) is an educational NGO working to “foster awareness of an often-overlooked aspect of WWII history, in the interest of furthering the values of justice, peace, and reconciliation, both for survivors of the past and for those who shape the historical narratives of the present and future.”