Secondary menu

The Neocolonial Underbelly of International Human Rights Advocacy

On legal education, human rights, and the Third World

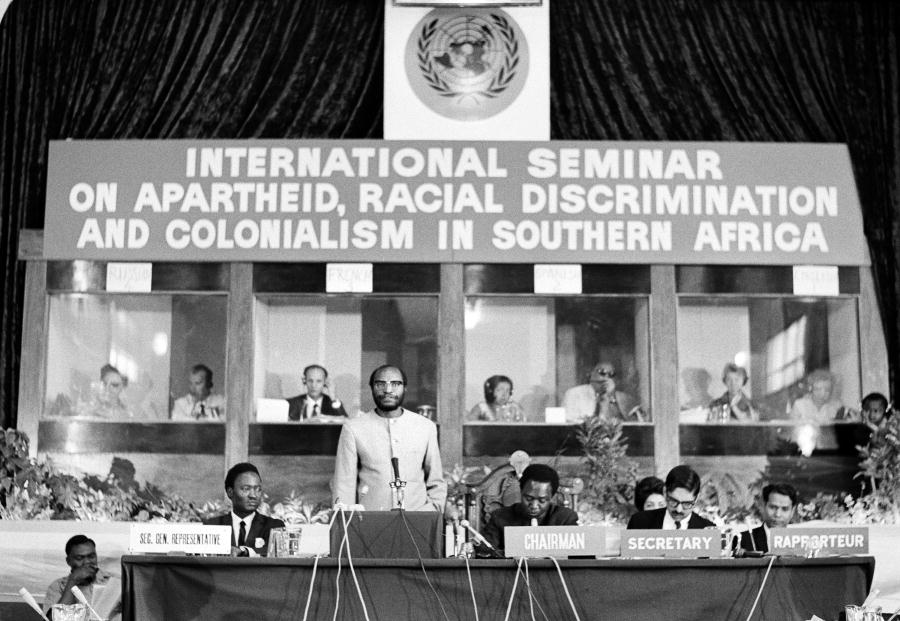

(Photo Credit: Jeff Riedel / UN Photos)

Throughout our legal education, law students are lured by a fantasy of international law that conceals a more shameful story. The former regales us with a legal order forged by a community of equal and sovereign nation-states and fortified by a commitment to peace and cooperation. In this narrative, international law is a legitimate expression of universal values, righteously defended by a fair and impartial guardian. This regime, we are told, is a just and equitable form of global governance.

The other telling of international law uproots this romantic fiction, disturbing its settled surface to unearth—in one sense, quite literally一the bones beneath. It is a macabre account of a legal order fashioned to facilitate colonial conquest by legitimizing economic exploitation, territorial dispossession, and cultural subordination. Universality is but a smokescreen that allows the insidious imposition of a racialized hierarchy, entrenching the dominance of Western interests and prejudices. Most significantly, this story is narrated in the language of Third World peoples who have long been denied a voice in international law as they struggle against a coercive and parasitic world order.

Notwithstanding our hopes for international justice, law students are inevitably hauled into these violent machinations. As such, we are forced to contend with our part in reinforcing unequal global power relations.

Legal professionals in the West wrestle with the ongoing shocks of imperialism and neocolonialism in the Third World through various interventions. International human rights organizations are plentiful, and their ambitions and ethical configurations are diverse. As this issue of Rights Review reveals, students at the International Human Rights Program take part in several such interventions. Working groups help compile legal resources for open-source databases, conduct legal research for refugee claims, and verify evidence to be used in legal proceedings to prosecute war crimes, among other undertakings.

However, an uncomfortable truth that underlies projects like these is that the power of legal professionals necessarily relies on the inaccessibility of the law. When legal systems and knowledge are mystified, rendering it more difficult for oppressed peoples to advocate for themselves, the role of lawyers assumes more significance. We have a vested interest in the law remaining opaque and untraversable. In the international law realm, this asymmetry is sharpest between lawyers in the West and marginalized communities in the Third World.

Thus, the overarching challenge is how human rights initiatives involving legal professionals in the West resist the unjust underpinnings of international law. Who is making decisions? With whose consent are they making those decisions? By what criteria are they making those decisions? What principles and experiences shape these criteria and their application? Without fully attending to these issues, these initiatives risk reinscribing the politics of domination that animate our international legal order. Moreover, it is worth contemplating how these projects meaningfully contest the material divisions that separate the West from the Third World—namely, who has access to legal knowledge and the law, and who decides what constitutes legal knowledge and the law.

The ultimate danger of the West’s contributions to international human rights law is the further disempowerment and displacement of Third World peoples as full participants in their governance. As law students, without grappling with what it means to decenter the West in our legal work, we are unable to reimagine the international legal order as one that reflects the full humanity and dignity of people in the Third World. Thus, it is imperative that we critically examine our role in this fundamentally unjust system and take leadership from locally grounded progressive movements in the spirit of prefiguration.

Above all else, we must retell the past, present, and future of international law through the emancipatory aspirations of the Third World.

This piece references the work of Third World Approaches to International Law (TWAIL) scholars, including James T. Gathii, Makau Mutua, Obiora Okafor, Antony Anghie, B.S. Chimni, and others.