Secondary menu

In Search of a Better World: A Film Discussion with Payam Akhavan

By: Alex Foulger-Fort (2L) and Andrew Parker (2L)

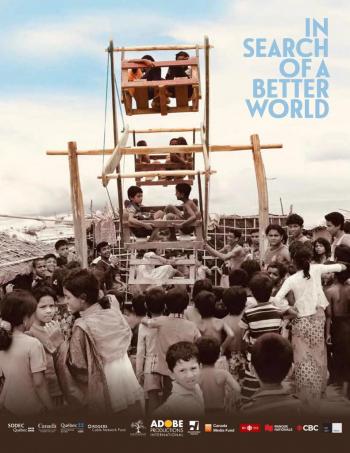

On June 17, 2022, Massey College hosted a screening of In Search of a Better World (2021). Directed by Robbie Hart and Mary Darling and inspired by Payam Akhavan’s book, In Search of a Better World: A Human Rights Odyssey (House of Anansi Press, 2017), the film documents Akhavan’s journey from a precocious teenager eager to fit in with his Torontonian peers to a seasoned international lawyer. The screening was followed by a panel discussion reflecting on the current state of human rights in the world.

In Search of a Better World follows the journey of international lawyer and human rights defender Payam Akhavan. Akhavan’s background and his motivation to defend human rights are inspiring, and he is telling his story at a timely moment in international relations.

Born in Tehran, Akhavan and his family fled Iran when he was nine years old. Pressured into leaving by the threat of persecution due to their Bahá’í faith, they eventually settled in Toronto, though stories from Iran would continue to haunt them. As Akhavan remembers, “we felt like our world was encircled with gloom with all the terrible news we heard from Iran and the destruction of that world of innocence.”

Growing up in Canada, Akhavan followed reports of the execution of Mona Mahmudnizhad, a 16 year-old Bahá’í activist hanged by Iranian authorities for speaking out against the persecution of her community. For Akhavan, that was a “turning point.” Mahmudnizhad’s bravery in choosing to die rather than betray her faith served as a catalyst for his career in human rights, and remains a source of inspiration for him today.

Akhavan has followed Mahmudnizhad’s example of bravery and conviction throughout his career. He splits his time between Montreal, where he serves as a professor at McGill University Faculty of Law, and wherever else his work takes him. Lately this has meant traveling to Bangladesh to gather evidence of the Rohingya genocide and document survivors’ stories

Akhavan’s semi-nomadic lifestyle reflects his fraught connection with the idea of “home.” Few anchors tie him down geographically. A grand piano in a mostly empty Montreal apartment is among his few material possessions – his portal “to beautiful places.” Family is, of course, another anchor. The documentary introduces us to Akhavan’s parents, whose cooking serves as a much-appreciated respite from the airplane food that he has become accustomed to as a jetlagged international lawyer. Through such details, In Search of a Better World beautifully chronicles Akhavan’s relentless pursuit of justice and the price at which it comes (one he gladly pays).

Following the screening, Rachel Pulfer, executive director of Journalists for Human Rights, moderated a “conversation about better.” Bob Rae, Canada’s Ambassador to the UN, opened the discussion virtually, introducing the five panelists: Akhavan himself; Farida Deif, Canada Director at Human Rights Watch; James Orbinski, professor at York University and Director of the Dahdaleh Institute for Global Health Research;Bob Watts, Vice President of Indigenous Relations at the Nuclear Waste Management Organization, adjunct professor and distinguished fellow at Queen’s University, and Chair of the Downie & Wenjack Fund; and Marzieh Darling-Donnelly, student and youth activist who has spoken at the UN and COP26.

The panelists were asked a number of questions from the moderator and the audience. Their contributions are summarized below:

Speaking on what is needed to achieve better human rights outcomes in our global institutions of justice, Akhavan pointed out where we currently fall short. Existing global institutions lack the capacity to address emerging problems. A lack of political will, coupled with myopic political elites and an apathetic public, combine to stymie progress in this arena. Far too often, institution building is calamity-driven, with new institutions arising out of our collective horror at witnessing yet another mass human rights violation. Akhavan cites the establishment of the International Criminal Court following the atrocities in Yugoslavia as an example. For Akhavan, creating social movements with a profound sense of empathy and a global vision are the key to achieving “better.”

Farida Deif discussed her role advocating for a “human rights respecting” foreign policy and identified key pathways for forging a future in this direction. Deif highlighted Canadian society’s response to the war in Ukraine – watching with outrage and steadfastly supporting the Trudeau government’s dedication to providing aid to Ukrainians. This reaction, she says, should be the benchmark for our humanitarian response to every crisis. Deif emphasized the importance of ensuring that the experiences of those impacted by human rights violations remain front and center during our response to these crises. International justice is not confined to “the courtrooms and the Hague,” but rather lies in making sure that victims’ voices are heard.

Bob Watts addressed what Canadians can do individually and collectively to ensure that Indigenous rights are respected today. He identified the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s 94 Calls to Action as a useful source for Canadians to find their own, as Gord Downie once said, “reconciliaction.” Reflecting on the concept of justice, Watts described how, while talking and healing may be an important part of a victim’s journey, ultimately “justice is justice.” Watts put forth his model for decision-making, which focuses on “those things that are symbolic, those things that are substantive, and those things that are systemic.” For Watts, a fourth “S” – spirit – is vital in unifying us collectively to make necessary social change.

Speaking from a global health perspective, James Orbinski reflected on what we have learned from the COVID-19 pandemic. Echoing Watts’s observations, he posited that we are continuing to face a “crisis of spirit.” Orbinski reemphasized Akhavan’s perspective by noting that, historically, change has often occurred as a response to serious upheaval. The League of Nations and subsequently the UN, for instance, were created in response to crises. We are now faced with an opportunity to reform and rebuild our global institutions, re-equipping the outdated ones that we rely on. Orbinski also highlighted the importance of the particular as well as the global: particular events, like the discovery of unmarked graves, or the actions of individuals, can have immense influence to spark change on a global scale.

Marzieh Darling-Donnelly, responding to a question about how older generations can best support and encourage young people, reflected on the prevalent feeling of hopelessness and anger among youth today. To Darling-Donnelly, this sense of anger is justified, but has begun to turn into dismay. She criticized the role of the media and political officials in contributing to this “tide of hopelessness.” Musing on how chiding young people to “be realistic” has often served to discourage them from getting involved and fighting for change, she underscored the importance of giving younger generations a voice and an opportunity to meaningfully participate, rather than treating their presence and contributions as a mere formal requirement to be met.

Akhavan’s story and each of the panelists’ insights amount to a call to action – a call for sustained and meaningful engagement with human rights issues across generations. For Akhavan, Mona Mahmudnizhad’s death in Shiraz in 1983 was a defining moment. For hundreds of Iranians today, the death of 22-year-old Mahsa Amini while in custody for wearing allegedly “improper” clothing has become an equally powerful turning point, as women take to the streets and protests spread across the country. In some ways, the upheaval of the past two years of the pandemic seems to be leveling off as we make the shift back to in-person interaction. Hopefully this call for a return to “normalcy” will not trigger a total reversion to the status quo ante and a loss of a crucial opportunity, as Orbinski pointed out, to reflect and reform.