Secondary menu

Our Summer with SASLAW Pro Bono

New perspectives on labour law

Constitutional Court, Johannesburg. A building designed to reflect the values of the new constitutional democracy.

Last summer, we participated in the fourth iteration of the South African Society for Labour Law (SASLAW) Pro Bono Canadian fellowship programme. SASLAW’s Pro Bono project is administered out of South Africa’s four labour courts and aims to assist unrepresented, indigent litigants who would not otherwise have access to justice. The free legal advice clinics are serviced by SASLAW’s volunteer attorneys on a rotational basis.

We spent two days each week at the embedded Pro Bono office in Johannesburg’s student district. Our tasks included administrative work, help with bringing in clients, and updating the internal client tracking system. The rest of the week was spent visiting law firms and organisations throughout the country.

In South Africa, the unemployment rate is approximately 35% (55% including informal workers). For comparison, Canada’s current unemployment rate is around 5%. There are a myriad of factors contributing to the country’s high unemployment rate, one of which is the legacy of apartheid. Apartheid translates to “apartness” in Afrikaans and refers to the system of institutionalized racial segregation that governed South Africa from 1948 to 1994. The system was premised on social stratification by race, which ensured South Africa was dominated politically, socially, and economically by the minority white population. The effects of apartheid cut across all aspects of life, from the segregation of public facilities and social events to housing, education, and employment opportunities.

Yet, the social and economic effects of apartheid continue, particularly in the labour sphere. We witnessed the racial divide while working at the Pro Bono office at the Labour Court where almost every client was Black, and the vast majority of judges and lawyers were white. Even at the Pro Bono office, there seemed to be barriers to accessing justice at every turn. The travel necessary to access legal assistance was what often stuck out most to us. When collecting the sign-in sheet for the day's appointments, the arrival times were as early as 4 a.m., with many clients having slept outside the court to get an appointment. We met with individual clients and heard their concerns, translating these into demand letters for payment of owed wages. Often, we got to see how these letters, especially when printed on formal firm letterhead, would enable clients to resolve matters with employers without going through the incredibly lengthy court process.

We believe the aim of the program was to provide an in-depth understanding of the field of South African labour law from multiple perspectives. We met judges and visited historic legal landmarks, 14 law firms, 5 different Pro Bono offices, as well as union offices, factories, women’s shelters, and children’s homes across South Africa. We had the opportunity to engage with internal employer processes, such as disciplinary hearings, including those that involved government workers. We drafted formal lines of questions to support these hearings and arguments for court cases, consulting with practising attorneys and litigators. We also reviewed internal and external policies responsive to South Africa’s new initiatives to end gender-based violence and discrimination. Each day brought new opportunities to build our skills and our understanding of labour law. The following are only a fraction of the cases and opportunities we were exposed to, but each had a lasting impact on us:

Cheadle Thomspon & Haysom

One of the highlights of the fellowship was our week spent with Cheadle Thompson & Haysom, one of the few union-side labour law firms in the country. We met with one of the directors who had been with the firm since commencing her articles. She recounted to us the political origins of the firm and how it began as a mechanism to challenge the apartheid legal order at the time. She also relayed the story of Bhekisizwe (Bheki) Godfrey Mlangeni, a member of the firm’s legal team representing the Independent Board of Inquiry into Informal Repression. Bheki also represented various clients at the Harms Commission of Inquiry into the assassination squads of the then South African Police and South African Defence Force. Bheki was tragically assassinated in the course of this work in 1991. He was killed by an explosive device concealed in a cassette sent by the Vlakplaas Unit of the then South African Police. The director, working under Bheki at the time, informed us that she had offered to listen to the cassettes in his place. Her recount of this story stayed with us. The recency of the event put into perspective the proximity of the past from which the country is still trying to recover and rebuild.

Legal Resources Centre

Throughout the fellowship we also got to connect with leading human rights organisations throughout the country. In Durban and Johannesburg, we had the opportunity to meet with representatives of the Legal Resources Centre (LRC). They spoke to us about their focus on education and land, and how their organisation works through strategic litigation by building up a case from ground zero. They work on matters never previously litigated, and craft arguments through heavy research and attacking problems from multiple angles. At the LRC, we learned about the issues that have emerged as a result of the over 6,000 abandoned mines in South Africa. From an environmental perspective, these mines are not properly “restored” or “shut down” which means that chemicals leak into the local water supply. The mines are also at risk of collapse, and there are open mine shafts hundreds of feet deep with no demarcations or safety provisions to warn passersby. These mines negatively impact local flora – extending to impact the surrounding animal populations as well. Many people have died from chemical exposure tied to the mines. These abandoned sites are also a hotbed for illegal activity, attracting mining cartels engaged in violent crime and slave labour and crowding out artisanal miners who work sifting through leftover materials to get by. We were encouraged to bring this information back to Canada in order to spark conversation on the impacts of Western demand for precious metals and coal and how that has negatively impacted (and continues to impact) Africa.

Our visit to the Legal Resources Centre (LRC) in Durban.

Our visit to the Legal Resources Centre (LRC) in Durban.

Ndifuna Ukwazi

We learned more about the social conditions in South Africa through our work with Ndifuna Ukwazi, an activist organisation and law centre that advocates for access to well-located land and affordable housing. One of the lawyers working for the organization, Jonty Cogger, walked us through the housing and land issues facing Capetonians and how current practices are perpetuating spatial apartheid for poor, working-class families and communities. We got to see the effects of their work on the ground by meeting with clients living in an encampment whose rights to remain on the land were protected by virtue of a recently secured court order. Due to the work previously done by Jonty, the members of the encampment were able to present laminated copies of their interdict to the police which prevented them from being forcibly removed.

Through Ndifuna Ukwazi we also learned about the “reclaim our city” movement. The movement started with an occupation of an old hospital building to put pressure on the government to transform unused buildings into affordable housing. We had the opportunity to visit the building and meet some of the people involved in the movement. The more than 250 rooms had been occupied for over 5 years. The community had created individual living accomodations in the old hospital rooms along with a school/kresh (child care centre), movie-viewing spaces, and gardens. It was amazing to see what had been accomplished with very limited resources. We were especially inspired by a housing activist residing in the building who, with the support of Ndifuna Ukwazi, was hosting legal education workshops to inform fellow residents of their rights.

Pro Bono Trial

At Webber Wentzel, a leading law firm in the country, we had the privilege to sit in on the Pro Bono team while they worked on a trial involving the assault, torture and use of solitary confinement on multiple prisoners (see Llewellyn Smith and five others v. The Minister of Justice and Correctional Services). Based on the Correctional Services Act, there is a differentiation between “solitary confinement” (which is no longer permitted) and segregation. Prisoners placed in segregation require special provisions dictated under the Correctional Services Act. The Act specifically indicates that prisoners must receive adequate medical treatment and immediate medical examination if force is used against them. A point of contention at trial was whether the prisoners should have been visited by a nurse or doctor daily while in segregation. It was also argued that much of the full extent of the injuries had been hidden by the nursing staff. We were able to see the submissions by the nurses and hear their cross-examinations, which revealed inconsistencies in their rehearsed statements when they went off script. However, even the lawyers that were cross-examining the nurses recognized the difficult position they were in, given that some of them were still working for the prison and most likely did not have a real choice but to comply with the cover up.

Conclusion

Our learning took place both inside and outside of the workplace. We were often confronted with uncomfortable truths about the law’s potential for abuse and its undeniable role in a history of systematic oppression with which South Africa continues to grapple. At the same time, we saw how powerful the law can be in championing the principles that underpin the South African Constitution, now considered one of the most progressive in the world. We are incredibly grateful to SASLAW, its partnering firms, UofT, and the various stakeholders that made this fellowship possible, and for the enriching perspectives that we gained in the process.

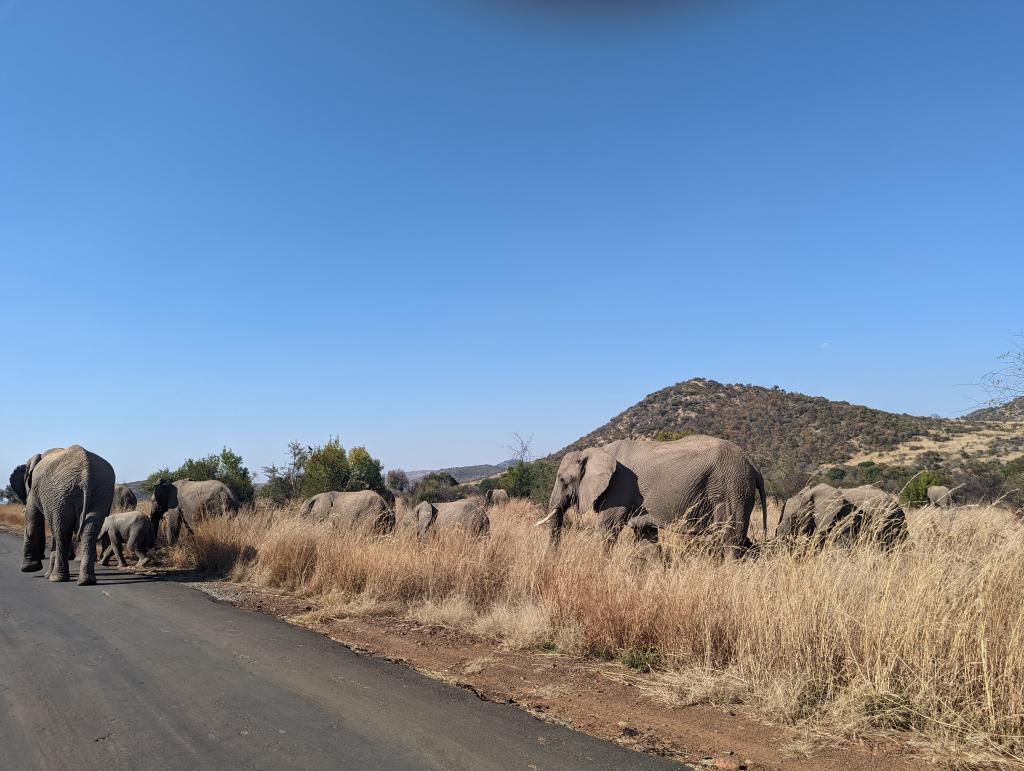

A herd of elephants crossing in front of our car.

A herd of elephants crossing in front of our car.