Secondary menu

Responding to the Audit Report: Taking Kafka out of Immigration Detention

Anne-Rachelle Boulanger (4L JD/MGA)

Ricardo Scotland, a refugee claimant from Barbados, spent 18 months in maximum-security jail. He was serving an administrative detention, awaiting his refugee hearing. Through multiple immigration detention review hearings, the Immigration and Refugee Board’s Immigration Division (Tribunal) appeared to find ample justification to continue Mr. Scotland’s detention. According to the Tribunal, he was a flight risk. He had been criminally charged, and had apparently breached his immigration and bail conditions. However, in the habeas corpus decision regarding Mr. Scotland’s detention, Justice Edward Morgan found that, “As with Kafka’s protagonist, Joseph K, no one knows why he is detained.”

“Although the government cannot provide a clear rationale for Mr. Scotland’s initial or continued detention, the reason for this lack of clarity is itself clear to me: there is no rationale. Mr. Scotland is being held in prison for no real reason at all.” – Justice Edward Morgan

The Report of the 2017/2018 External Audit for Detention Reviews [Audit Report], released July 20, 2018, identified numerous procedural fairness issues in immigration detention review hearings. In its review of 312 detention review hearings and decisions, the Audit Report found evidence of Tribunal Members relying uncritically on Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA) Hearings Officers’ findings; Tribunal members failing to decide afresh and over-relying on previous decisions; Tribunal members making inaccurate and inconsistent factual findings; and detainees facing barriers to hear and present evidence. Mr. Scotland’s case is but one example.

Mr. Scotland was never convicted of a crime. His criminal charges were either withdrawn, stayed, or acquitted. CBSA’s allegations that Mr. Scotland breached his bail conditions were unfounded. Yet, in his detention review hearings, these facts bore little weight. Tribunal Members made decisions without adequate evidence, and relied heavily on CBSA allegations while confirming previous Tribunal decisions. At one hearing, the CBSA Hearings Officer claimed that Mr. Scotland was not credible, characterizing his stayed criminal charges in the following way: “no guilt was found but no innocence was found either.” At another, the Member stated that “[…] CBSA is being very technical although it is within their right to find a breach if they find it to be a breach.”

“[…] Arrest and criminal charges without a conviction amount to innocence; a breach of bail conditions that turn out to no longer be in force is a non-breach of bail; pre-trial custody is not a change of address; an inadvertent error is not an intentional, morally culpable act. These cannot logically and legally be held against a detainee on an ongoing basis.” – Justice Edward Morgan

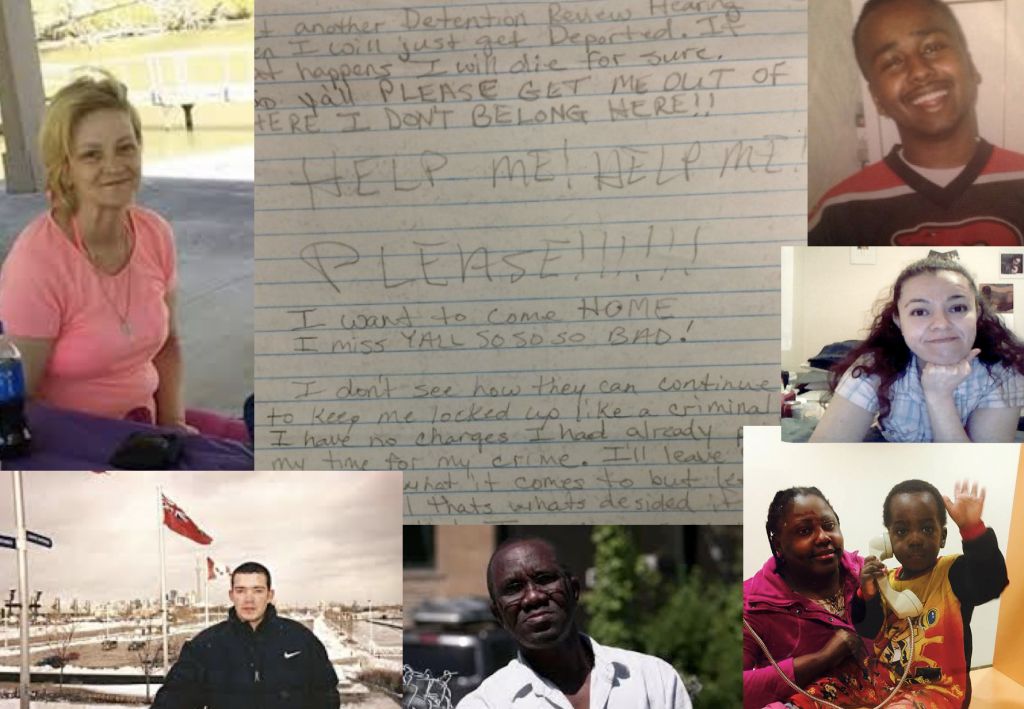

Hanna Gros' presentation at the Immigration Detention Symposium, March 2019, depicting former immigration detainees and a detainee's handwritten letter. Credit: Hanna Gros.

Since September 2018, Hanna Gros, researcher with the International Human Rights Program (IHRP), has led a joint response to this Kafkaesque regime. The IHRP, along with the David Asper Centre for Constitutional Rights, the Canadian Association for Refugee Lawyers and the Refugee Law Office of Legal Aid Ontario, are collaborating on this report, set to be released in the spring of 2019. The report will provide recommendations regarding meaningful safeguards of procedural fairness in immigration detention review hearings. The aim is to protect others from the kind of arbitrary process that Mr. Scotland endured.

In developing the report and recommendations, I assisted Ms. Gros in conducting research and interviewing immigration and refugee lawyers. Our starting point was to understand the interests at stake, and the safeguards in place to protect them. A comparison to the criminal justice system is illustrative. Both detention review hearings and the criminal justice system implicate individuals’ liberty interests. In fact, many immigration detainees are held in the same jails as criminally accused and convicted persons. Yet, the criminal justice system provides far more meaningful protections against arbitrary deprivation of liberty.

In the criminal context, a trial is governed by rules of evidence, procedural rights and principles of fundamental justice. In the immigration context, the Tribunal is not bound by any technical or legal rules of evidence, and may decide to continue detention on the basis of evidence that it considers to be credible and trustworthy in the circumstances. Every lawyer we interviewed indicated that Tribunal adjudicators rely on hearsay evidence in every single decision - evidence which is often barred in a criminal trial. Moreover, immigration detainees may be detained indefinitely. There is no legislated maximum length of time immigration detainees can spend behind bars - last year, Ebrahim Toure, a refugee claimant, was freed after over five years in detention. The longest instance of detention was 11 years.

Despite the absence of procedural safeguards afforded to non-citizens, courts have found that the immigration detention regime, as laid out in the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act, complies with Charter requirements. The regime is administrative in nature and premised on expediency. As such, it affords a large degree of discretion to Tribunal Members. It is the way that discretion has been exercised that has contributed to the arbitrary detention of many non-citizen individuals.

During the course of our interviews with lawyers, it became readily apparent that the problem goes well beyond lacking safeguards in the detention review process; a primary problem is one of culture. The lawyers repeatedly cited Tribunal Members’ willingness to rely uncritically on CBSA evidence, and to deem detainees to be liars.

The aim of the report is to establish robust legal measures that will protect individuals from a culture that is to their detriment – a culture that has been allowed to flourish in the absence of procedural safeguards. The report will be an important step towards holding Canada accountable to its Charter values and international human rights standards.

More importantly, however, it will be crucial to recognize the human impact of arbitrary and indefinite detention. The Supreme Court has held that right to liberty touches “the core of what it means to be an autonomous human being.” But if non-citizens can be deprived of their liberty for months and years, without meaningful recourse for review of their detention, what is the value of the right to liberty in Canada?