Secondary menu

The Right to Water: The Ongoing Fight of Indigenous and Northern Communities

A report on the Canadian Law School Conference event on the human right to water

By:

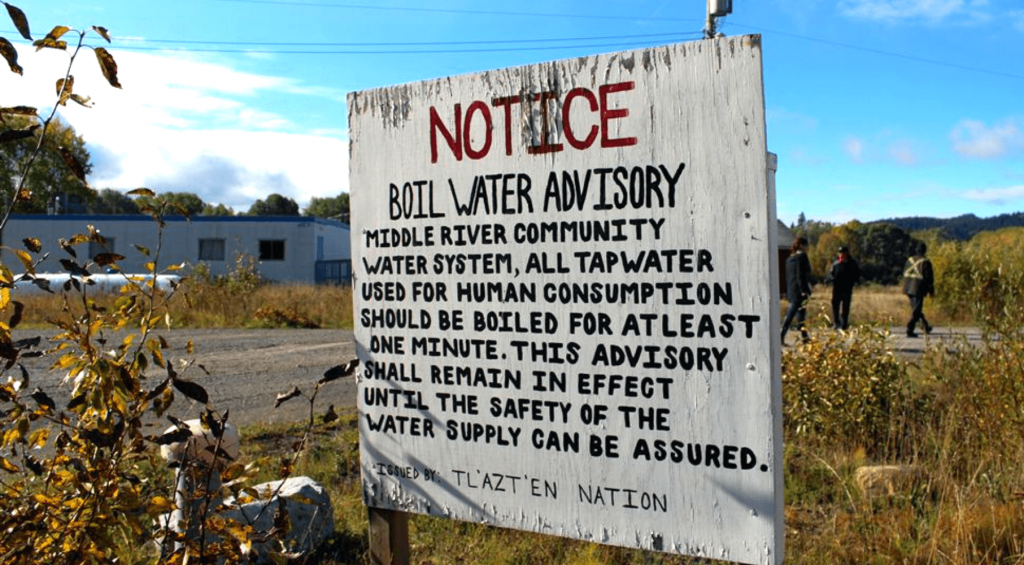

(Photo courtesy of the MacDonald Laurier Institute)

(Photo courtesy of the MacDonald Laurier Institute)

Human Rights Watch published a report titled “The Human Right to Water: A Guide for First Nations Communities and Advocates” in October 2019. The report builds on the findings of the United Nations Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR)’s February 2016 review of Canada in which the body highlighted “the restricted access to safe drinking water and sanitation by the First Nations as well as the lack of water regulations for the First Nations people living on reserves.”

The CESCR recommended that the government of Canada make changes to ensure Indigenous communities’ access to safe drinking water and sanitation, while creating spaces for these communities to be actively involved in planning and management. The body also noted not only the economic importance of water, but also the cultural significance of water to Indigenous traditions.

The human right to water includes the right of all individuals to “available, accessible, safe, acceptable and affordable” sources of drinking water and water for personal and domestic usage as well as sanitation facilities without discrimination. The Special Rapporteur on the Human Rights to Safe Drinking Water and Sanitation calls for “an explicit focus on the most disadvantaged and marginalized, as well as an emphasis on participation, empowerment, accountability and transparency.”

Canada’s inability to uphold Indigenous and remote communities’ access to water and sanitation is particularly appalling because of how water-rich the country is. Ontario has access to the Great Lakes, which alone constitute approximately 18 percent of the world’s fresh surface water. Furthermore, Canada is currently ranked tenth in the world by gross domestic product and has positioned itself as a country with human rights at the forefront of its domestic and global policy agenda. Canada has ratified:

- International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR);

- Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW);

- Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC);

- Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD);

- and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR)

The Government has also endorsed the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP). All of these sources of international law offer guarantees related to the human right to water and sanitation.

At the outset of this excellent panel hosted on February 28 by students from the Bora Laskin Faculty of Law at Lakehead University, Meera Karunananthan, Director of the Blue Planet Project, noted that human rights are not cure-all, referencing Dr. Samuel Moyn who believes human rights to be the floor, not the ceiling of righting injustice and inequality. Karunananthan explained that human rights are an important tool in the fight for clean water but not the only one.

The tools of reconciliation, redistribution, and decolonization are most relevant and human rights should fit into this framework. All three panelists emphasized the importance of self-government and communal rights in these discussions. Karunananthan concluded by saying that Indigenous relationships to water should not be exclusively mediated by the Canadian state. The right to water should include the right to sovereignty over ground water, lakes and rivers, and the land.

The right to water is only a recently recognized right, despite decades of advocacy working to establish it formally. Only in 2010, after a huge push by organizations around the world opposing privatization of water and sanitation, did the Campaign for the Human Right to Water begin.

Karunananthan reiterated that history shows that this right is not always the correct tool for the job. Successful campaigns and protests in Uruguay and Botswana show a model for the domestic codification of the right to water, for the prohibition of privatization, and for the use of the right to water to challenge the expulsion of Indigenous communities, but many other countries have not been successful in these efforts.

In the Indigenous context, the right to water holds unique meaning. Dr. Bruce McIvor, principal of First Peoples Law Corporation, noted that, although he is not an expert in the plethora of Indigenous legal traditions and their relationships to water, he has learned through his work in Aboriginal law how significant water is in the culture and ceremonies of Indigenous groups.

In a case involving the development of transmission lines through First Nation territory, the opening up of this land to non-Indigenous populations brought ATV drivers straight through the culturally significant Women’s Water Ceremony, with children and elders present. The community no longer felt safe accessing their land for these ceremonies.

Stephanie Willsey, counsel at McCarthy Tétrault LLP, underscored the devastation to Indigenous culture that has arisen from unsafe drinking water. With the local water sources polluted and unsafe to drink or touch, a First Nations community participating in the national class action against the Canadian Government attempted to keep their traditions alive using bottled water. This loses meaning and, in turn, the connection to many of the community members, especially the youth. Without the ability to pass on the traditions through water ceremonies, intergenerational effects of this pollution will only grow.

Finally, putting the right to water into the contemporary context of COVID-19, all three panelists at this event criticized the false narrative that this pandemic is “The Great Equalizer.” Clearly, this pandemic disproportionately affects Indigenous peoples, people of colour, and all those experiencing the intersections of race, poverty, disability, age, gender, and sexual orientation. The pandemic only fuels the pre-existing water crisis, which has not received the necessary attention from domestic governments.

When affected communities are forced into worsening circumstances, the panelists noted that they show resilience, determination, and creativity. The same cannot be said for the Canadian government addressing (or failing to address) these problems. Throughout this global pandemic, Dr. McIvor has witnessed the government use COVID-19 as an excuse to delay files, deny assistance, and prolong suffering.

Dr. McIvor also noted that the government’s frequent excuse that “they do not have the money” bears little weight now that we see billions of dollars become available to middle class, non-Indigenous people in this global pandemic. The money has always been there. The political will has never.

Sadly, the issues highlighted by the panelists are simultaneously shocking and unsurprising. The CESCR and HRW reported on the lack of meaningful access to safe drinking water and sanitation services for Indigenous and other rural communities in 2016, but this was no revelation to the communities in question; unequal development and protections among Canadians have been the story for as long as settlers first came to Turtle Island.

It is up for the Canadian federal and provincial governments to take aggressive action to rectify the situation and uphold a human right that has been formally recognized for over a decade now, and yet, Indigenous communities should not hold their breath and must take matters into their own hands.