Secondary menu

Roundtable: Professor Kent Roach's Vision for Human Rights Remedies

Top legal minds reflect on his most recent book on human rights

“We live in a world rich in rights and poor in remedies,” states Professor Kent Roach in his book, Remedies for Human Rights Violations: A Two Track Approach to Supra-national and Domestic Law.

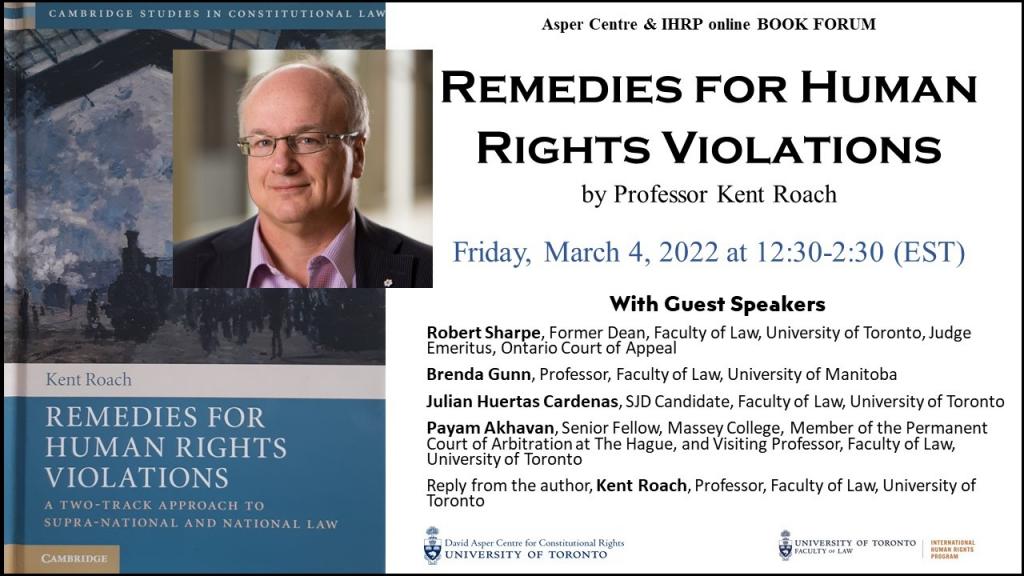

In a roundtable discussion held on March 4, Justice Robert J. Sharpe appeared to share the sentiment. In his view, due to this plethora of rights and the legal community’s emphasis on proving violations, remedies are often left as secondary considerations. Also in attendance were Professor Brenda Gunn (Métis, Treaty 1 territories – Manitoba), Associate Professor at the University of Manitoba Faculty of Law, and University of Toronto’s own Professor Payam Akhavan, Senior Fellow at Massey College, Member of the Permanent Court of Arbitration at The Hague, and Special Advisor on Genocide to the Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court.

Prof. Roach’s latest book takes a step toward correcting this imbalance. Remedies for Human Rights Violations refines existing remedies and defends a compromise between the two traditional tracks of human rights (HR) remedies in Canadian and international law. Prof. Roach highlights remedies that not only declare injustices but facilitate their rectification. He envisions these remedies—“declarations plus”—as mitigating the risk of courts overstepping their competencies as compared to the application of traditional remedies alone.

The following presents a summary of the feedback offered by the three legal scholars who discussed Remedies for Human Rights Violations during the roundtable event, followed by Prof. Roach’s response.

Critiques of Existing Human Rights Remedies

A short summary of the problem that Prof. Roach is addressing is warranted. At the roundtable, Justice Sharpe presented the two traditional tracks of HR remedies, highlighting their strengths and weaknesses.

Track one involves a judge simply declaring a rights violation. An advantage of stopping there is that the court knows it is still well within its bounds and can place pressure on the impugned institution to change. However, declaratory relief has its disadvantages. Institutions may pay no regard to the court’s declaration, which might place the HR legal process into disrepute. Moreover, institutions are only accountable to themselves to implement reform following the declaration.

Track two involves a court ordering remedies for HR violations. For instance, after declaring a violation, courts will often order specific reforms of the institution(s) at fault to remedy the violation and prevent further occurrences. These orders can vary from compensation to ordering complete systemic overhaul. The latter, according to Justice Sharpe, is a trap of track two: systemic change is complex and multidimensional, and courts are often ill-equipped to order appropriate remedies in that space. However, if a court stops at compensation or simply strikes down a law, the remedy could be inadequate or compromise a legitimate law.

The risks of an inadequate, inappropriate or overambitious remedy are what, in Justice Sharpe’s opinion, would have made him hesitate to use the second track of HR remedies. However, in his view, Prof. Roach’s synthesis of both tracks could empower judges to order remedies beyond declaratory relief with greater confidence.

Professor Roach’s Ideal Remedy

According to Justice Sharpe, Prof. Roach’s view of the two-track approach presents a logical compromise. Instead of viewing declarations and remedy orders as distinct, they could be combined. For Prof. Roach, this can look like a “declaration plus,” the term he uses for his proposed two-track approach. Resorting to such a remedy, the court would declare a HR violation while also ruling that it will supervise, rather than determine, the institutional reform used to remedy the violation. In this way, the court avoids ordering remedies with which it has little expertise or ordering inadequate remedies. At the same time, a “declaration plus” does not leave survivors of violations without hope for remedies. Under Prof. Roach’s approach, reform would be guided by those familiar with the institution rather than the court. Supervision, Justice Sharpe agrees, puts more pressure on an institution to reform than a simple declaration.

Suggestions from the Roundtable

While Prof. Roach’s approach was praised as nuanced and valuable by the roundtable participants, the discussion of his book brought some thought-provoking suggestions.

Prof. Gunn shared her concern that Prof. Roach’s two-track approach might facilitate compromises that are not the most conducive to reconciliation with Indigenous peoples whose rights have been violated. Her belief is that Prof. Roach’s inclusion of a proportionality element in the supervision of remedies could be used to subvert the interests of Indigenous peoples. For instance, when majority interests favour decision-making that benefits non-Indigenous peoples, proportionality could slow reconciliation in Canada.

Prof. Akhavan argued that declarations (track one only) are important remedies in themselves. According to him, they can be especially useful in non-liberal societies where the line between declaratory relief and remedy is blurred, and where the persecution of some minorities has become entrenched. In these contexts, ordering anything more than a declaration would likely gain little traction within an impugned institution. Prof. Akhavan argued that while institutional change may not yet be possible in these societies, declarations could help initiate truth commissions. Such commissions could be foundational to greater societal buy-in to contesting human rights abuses.

Professor Roach’s Response

Prof. Roach acknowledged Justice Sharpe’s preference for using track one (declaratory) remedies throughout his career. Prof. Roach validated this approach and affirmed that a judge can bring about change by declaring a violation and saying that an institution has insufficiently reformed to avoid recurrence. However, Prof. Roach thought it was most important for judges to keep in mind that declarations themselves do not lead to respect for human rights.

Prof. Roach also agreed with Prof. Akhavan on the utility of declaratory relief in non-liberal-democratic contexts. He expressed that he might have improved his book by including greater discussion on the use of truth itself as a remedy. Prof. Roach seemed fully on board with Prof. Akhavan’s point: declarations can be powerful on their own, especially when discrimination is imbued in a society.

Finally, Prof. Roach addressed Prof. Gunn’s concern surrounding his inclusion of proportionality among the principles judges can use when supervising institutional reforms. He recognized the importance of this question while sharing a different take on the operation of proportionality in his two-track approach. He explained that the proportionality tool was included to prioritise, rather than downplay, minority interests and the interests of Indigenous peoples. While Prof. Roach did not elaborate on how this would be achieved, he did note a historic situation where Cree rights were trampled over during a Quebec energy project. This was justified at the time for being what was best for Quebec as a whole. This is exactly the kind of situation that Prof. Roach feels his approach could address, in part through its emphasis on proportionality.

In sum, by putting forward this ideal synthesis of the two tracks of HR remedies, declarations and institutional reforms—the “declaration plus”—Prof. Roach advocates for remedies that are more ambitious than a declaration and that empower those with institutional knowledge to prevent further violations. In this way, it is a more fine-tuned, adaptable and appropriate remedy for a judge to enforce. Though it may not be employable in all contexts, the emphasis on proportionality may be an effective way to ensure that minority groups, including Indigenous peoples, get remedies that acknowledge historic oppression. Finally, while Prof. Roach believes that remedies may continue to fail, he feels that as they are continually adapted, they will engender higher compliance and more effective outcomes for survivors of violations.