Secondary menu

Strategies for Justice in a "Period of Darkness"

Recap on "Seeking Accountability in Conflict" Panel Discussion on 4 December 2019

Julie Lowenstein (3L)

On 4 December 2019, Human Rights Watch (HRW) and the International Human Rights Program (IHRP) co-hosted a dynamic panel of human rights experts to discuss the critical need for justice and accountability in the world’s worst conflicts. Entitled “Seeking Accountability in Conflict,” the panel featured Allan Rock (Professor at the University of Ottawa, Faculty of Law and former Canadian ambassador to the United Nations), Balkees Jarrah (senior counsel for the International Justice Program at HRW) and Param Preet Singh (associate director of HRW’s International Justice Program) in conversation with moderator Nahlah Ayed (award-winning foreign reporter for the CBC and host of the CBC podcast Ideas). The panelists set out to discuss how civil society organizations can play a pivotal role in seizing—and sometimes creating—opportunities to bring those responsible for international injustices accountable.

Left to Right: Allan Rock, Balkees Jarrah, Nahlah Ayed, and Param Preet Singh (Credit: Alison Thornton, HRW Toronto)

Left to Right: Allan Rock, Balkees Jarrah, Nahlah Ayed, and Param Preet Singh (Credit: Alison Thornton, HRW Toronto)

The panel began with a somber, yet important, message: we are currently experiencing a global crisis of impunity. This “period of darkness,” as the panel called it, is characterized by a decrease in criminal accountability in the International Court of Justice (ICJ). As Jarrah explained, we are also seeing less of the kind of international public outrage in response to international injustices that we saw in the 1990s. At the same time, global crises—such as a possible genocide in Myanmar; abuses against civilians in Afghanistan and Syria; and government-led crimes against humanity in North Korea and the Philippines—demand accountability, even if justice remains difficult to achieve.

Rock cited a number of root sources for our current global trend of impunity. First, Rock explained, in the United States, President Trump can be resistant to campaigns for justice and international justice is often a “foreign concept” to his administration. For instance, the US government has been refusing visas for International Criminal Court (ICC) members investigating potential war crimes by US troops in Afghanistan. Second, the five permanent members of the UN Security Council—China, France, Russia, the United Kingdom and the United States, known as the P5—are either directly involved, or have a client state involved, in almost all current major world conflicts. The P5 states have veto powers for referrals to the ICC, meaning that they can block injustices from making their way into the criminal court. As Ayed pointed out, it also does not help that the United States never “signed on” to the ICC.

The panel soon turned to a more optimistic discussion, with Ayed asking the panelists to talk about cases that “keep them going” and “give them hope.” Singh spoke about activism she has seen in support of the key principles that the ICC and other similar judicial institutions stand for, such as the simple idea that people should not be able to get away with murder. For Jarrah, it is resilient people and victims that keep her going. For instance, while ISIS has committed horrific and unthinkable abuses of innocent people, and in particular of Yazidi people, Nadia Murad—a young Yazidi woman who has become a fierce advocate for justice for the crimes that she and her community have suffered—has become an international inspiration and the recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize. Rock spoke about how, despite the dearth of justice for the Rohingya people in Myanmar, an ICC prosecutor is attempting to achieve justice in the ICC by pursuing the theory that, while Myanmar is not a state party to the ICC, one of the crimes that the state has committed is forced deportation to Bangladesh, which is an ICC state party, and therefore the elements of the crime were not completed until deportees reached Bangladesh. Rock sees this type of novel approach for justice as encouraging and an example of a growing determination to end our global crisis of impunity.

(Credit: Alison Thornton, HRW Toronto)

(Credit: Alison Thornton, HRW Toronto)

As an organization, HRW is also trying to fight against our global impunity crisis by championing the institutions and architecture that make justice a reality, such as the ICC. For instance, HRW led a campaign to give the UN Security Council mandate over Syria. While that resolution was, unfortunately, vetoed by Russia and China, HRW is pursuing other avenues to bolster international justice institutions. The best results are achieved, the panelists agreed, when the UN works in partnership with large Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) to influence the P5 states.

Continuing with an optimistic tone, Ayed observed that there does seem to be the beginnings of a turn to try and achieve justice on the international stage. For instance, in France and Germany, we are seeing more cases of universal jurisdiction, whereby lawyers try and pursue cases for crimes even when there is no link between the crime and the country in which the lawyer is working. For instance, lawyers in South Africa have also tried to exercise universal jurisdiction to prosecute sexual violence under Robert Mugabe’s rule in Zimbabwe. In Canada, we have the War Crimes and Crimes Against Humanity Act, which enables anyone in Canada to be prosecuted for international war crimes or crimes against humanity.

On the theme of universal jurisdiction, Singh brought up current efforts by the Gambia to bring Myanmar to justice at the ICJ, alleging that it has breached obligations under the UN Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide. In fact, Singh explained, while this case winds its way through the ICJ docket, Gambia has asked for provisional injunctive measures aimed at stopping Myanmar from committing genocide and destroying evidence of genocide and war crimes. On 23 January 2020, the ICJ granted Gambia's request and ordered Myanmar to prevent all genocidal acts against Rohingya Muslims. These measures mark an important step in the fight for justice in Myanmar.

(Credit: Alison Thornton, HRW Toronto)

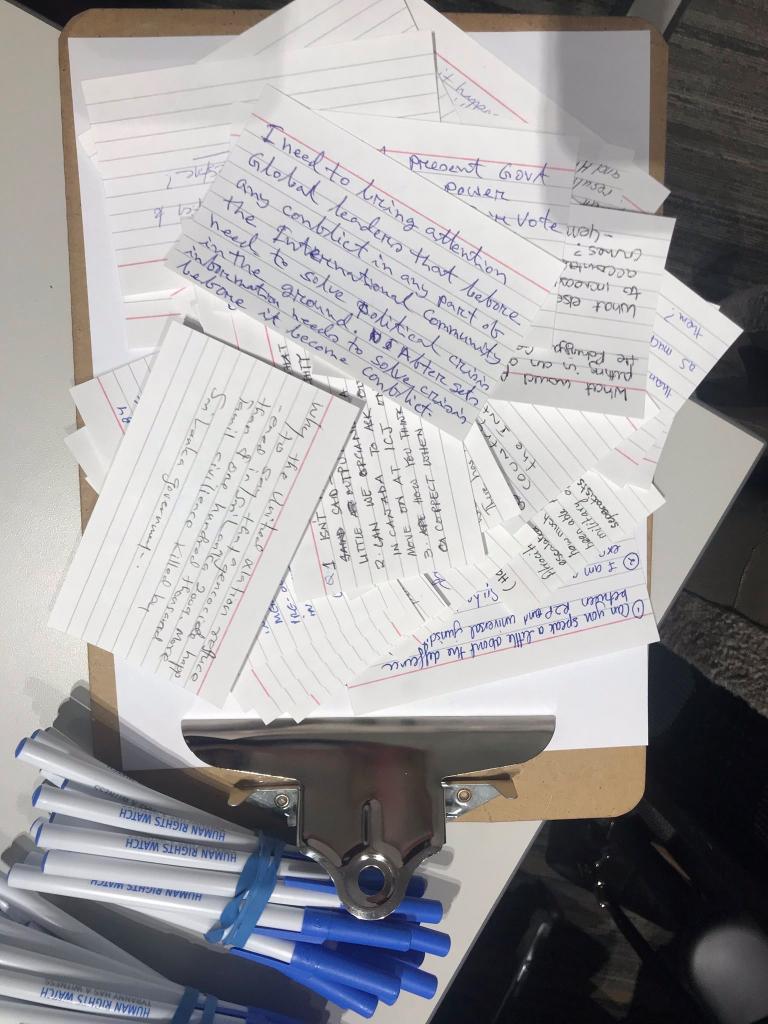

After an engaging and informative panel discussion, audience members—both in person and online—were full of questions, which they submitted to Ayed on cue cards and via twitter. Ayed started with a question about how people can educate themselves on the international justice crisis and help to advance the cause of international justice. Suggestions from the panelists include: reading HRW reports (available on HRW’s website) and reports from other NGOs in order to learn about the situations transpiring in different countries, becoming active members of HRW or other organization committed to international justice, and writing to Members of Parliament and pursuing other forms of advocacy to ensure that the Canadian government actively advances pursuits for international justice. For domestic human rights lawyers, universal jurisdiction prosecutions of international war crimes can be concrete avenues to advance international justice and can send the signal that Canada won’t be a safe haven for the perpetrators of these crimes.

The next audience question asked what role HRW is playing in advocating for ICC reform. Jarrah explained that, as the panel was going on, the rest of HRW’s international justice team was attending meetings with state parties in the Hague, advocating for a review process at the ICC that would identify challenges the institution is facing and generate recommendations to make the court more effective.

The final audience question hit on an important and topical subject: Given that big tech companies are the gatekeepers of world communication and can monitor world conversations with AI, what role might they play in helping to seek accountability in conflict areas? Singh noted that the dissemination of hate speech on Facebook has been a big issue in Myanmar. “While Facebook has vowed to do better,” Singh explained, “we can all point to examples of where they are not, and there remains a big tension in how to manage freedom of expression and hate speech.” Rock added that he thinks tech companies have a role in helping us with the early warnings of atrocities, suggesting that Facebook should collect and report speech that incites violence.

Overall, while the panel painted a grave picture of the international justice crisis, the discussion also offered glimmers of hope and strategies for the future. With the implementation of these strategies, and the cooperation of committed lawyers, individuals, governments, institutions and organizations like HRW, hopefully we will soon see a decrease in global impunity and an increase in justice for victims around the world.

(Credit: Alison Thornton, HRW Toronto)

(Credit: Alison Thornton, HRW Toronto)