Secondary menu

Vaccine Inequity and International Human Rights Law

Realizing the right to health through international cooperation

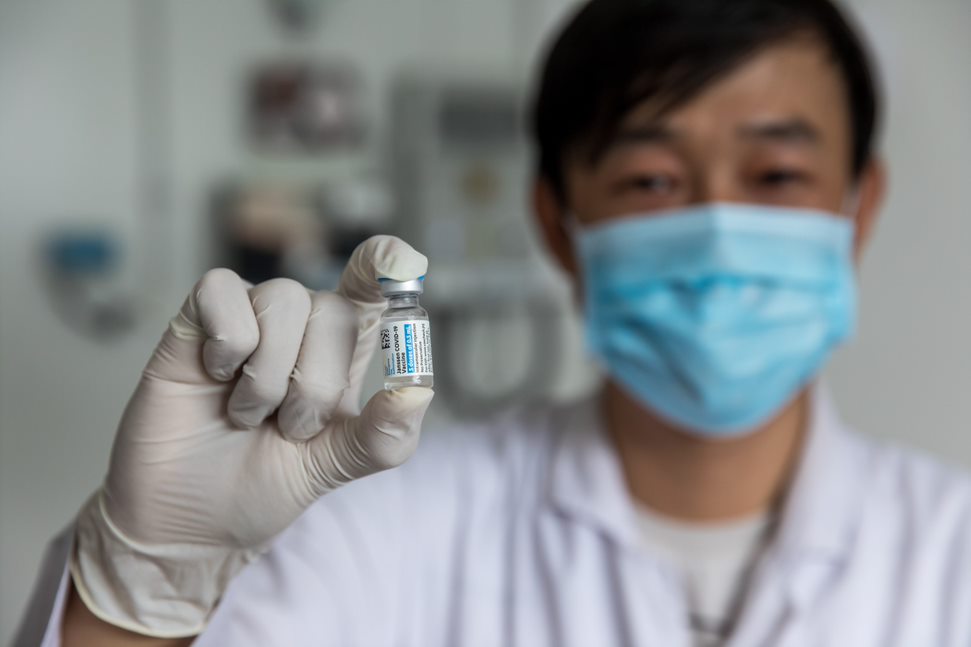

(Photo courtesy of U.S. Department of State)

Amid the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, vaccine inequity has become a pertinent international human rights issue.

At their May 27, 2021 meeting, the Strategic Advisory Group of Experts on Immunization, which advises the World Health Organization on global policies and strategies on the delivery of immunization, noted that high-income countries have administered sixty-nine times more doses of COVID-19 vaccines per inhabitant than low-income countries. A recent joint statement from several United Nations (UN) agencies highlighted the concerning implications of this development, emphasizing, “[t]his crisis of vaccine inequity is driving a dangerous divergence in COVID-19 survival rates and in the global economy.” Moreover, incomplete vaccination coverage promotes the emergence of COVID-19 variants, which could potentially reduce vaccine efficacy. Tellingly, UN Secretary-General António Guterres referred to vaccine inequity as “the biggest moral test before the global community.”

The causes behind the global vaccination gap are multivalent and complex. However, commentators have pointed to legal barriers, including intellectual property rights and export restrictions, as drivers of vaccine inequity. In turn, numerous voices have advocated for implementing transborder legal initiatives, such as multilateral legal agreements regarding vaccine purchasing, to allay vaccine inequity.

Indeed, the global vaccine gap has a range of implications from a legal perspective—particularly in terms of international human rights law. Significantly, the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, Michelle Bachelet, has articulated a human rights argument for multilateral cooperation regarding vaccine distribution. This article aims to briefly explore the key intersections between vaccine inequity and international human rights law.

To begin, health is recognized as a fundamental human right in international law. Article 25(1) of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948) provides that everyone has the right to a “standard of living adequate for the health and well-being” for themselves and their families. This right encompasses food, clothing, housing, medical care, and necessary social services, as well as the right to security in the event of unemployment, sickness, disability, widowhood, old age, or other lack of livelihood in circumstances beyond one’s control.

Further, Article 12 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) (1966) recognizes “the right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health.” Article 12, however, does not guarantee a right to be healthy. Rather, it outlines a series of freedoms and entitlements necessary to promote equal opportunity to enjoy the “highest attainable level of health” [emphasis added]. The concept of the “highest attainable” standard of health is qualified by the individual’s biological and socio-economic preconditions and available state resources.

What are the normative implications of these rights in the context of vaccine inequity? An understanding of the nexus between vaccine inequity and human rights can be gleaned from international legal instruments and interpretive documents. In particular, Article 12 of the ICESCR provides that the states party to that Convention must take certain steps to realize the right to health, including the prevention, treatment, and control of epidemic and other diseases. The control of diseases refers to individual and joint state efforts to pursue strategies of infectious disease control, such as immunization.

This responsibility has a cooperative, international dimension. States party to the ICESCR must respect the enjoyment of the right to health in other states and prevent third parties from violating this right in other states where they are able to influence the third parties through legal or political means, in accordance with international law.

The fact that the right to health encompasses disease control, coupled with this international dimension, implies that the right to health arguably precludes states party to the ICESCR from impeding other countries’ access to COVID-19 vaccines. For instance, states party to the ICESCR might be precluded from upholding intellectual property agreements that inhibit international vaccine distribution.

Yet, one could argue that whereas calls for an equitable distribution of COVID-19 vaccines tend to emphasize urgency, Article 12 of the ICESCR entails a “progressive realization” of the right to health over time. However, this means that states party to the ICESCR must nonetheless take concrete, deliberate, and targeted steps toward fully realizing the right to health, and act “as expeditiously and effectively as possible” in advancing this right.

For these reasons, the right to health as recognized in international law might entail interstate cooperation with respect to vaccine distribution. There are, however, several challenges associated with realizing the right to health in the context of vaccine inequity.

When it comes to international collaboration and the right to health, legal instruments and interpretive documents offer broad principles and general examples about how to proceed, but specific guidance regarding disease control and immunization is limited. Despite this challenge, the emergence of new structures in the international landscape amid the COVID-19 pandemic — such as the Multilateral Leaders Task Force on Scaling COVID-19 Tools, a joint initiative on the part of the International Monetary Fund, World Bank Group, World Health Organization, and World Trade Organization aiming to accelerate access to COVID-19 vaccines — may offer direction in the form of policy guidance and international norms.

Another challenge is that legal instruments which enshrine a right to health, such as the ICESCR, have not been ratified in every country. This can make enforcement of health rights through domestic legal institutions challenging. Additionally, there is a dearth of jurisprudence related to vaccination in the context of the right to health in international law. As a result, those who might wish to advance claims relating to vaccination and the right to health before international bodies have little to rely on in the way of precedent. Other barriers, including financial costs, time, and access to legal advice, may limit access to both international fora and domestic courts.

Despite these enforcement-related concerns, a human rights approach to vaccine distribution holds normative and discursive power. In fact, the International AIDS Society-Lancet Commission on Health and Human Rights advocates for a human rights approach to redressing vaccine inequity. In a 2021 article, the organization wrote:

Inequitable access to COVID-19 vaccines and therapeutics mirrors wider health and health-care inequities and is grounded in broader structural inequalities, putting some populations at greater risk than others… A human rights approach offers an alternative…

As science achieves such remarkable advances as the COVID-19 vaccines, it is compellingly clear that we cannot exclude our fellow human beings from benefiting from this advance. Allowing that kind of injustice is not only legally, politically, and morally unacceptable, but it also undermines all of our humanity.

These words speak to both the promise of a human rights-based approach and the pressing need to address vaccine inequity. Amid the upheaval created by the COVID-19 pandemic, one thing is certain: we must find the will to act now.